Potato Power

Grade 5

Presentation

Hypothesis

When a potato battery is heated, it will produce more electricity because heat will reduce resistance and allow electrons to flow more freely producing more power.

Research

What is Electricity?

- Electricity is the flow of electrons (negative charge) and protons (positive charge) (Britannica Kids).

- When the electrons flow between the negative and positive charge, it creates electricity (Britannica Kids).

What are the elements of a battery?

- To make a battery you need two different kinds of metal in a liquid or a paste. (Britannica Kids).

- The metal pieces are called electrodes. (Britannica Kids).

- The liquid or paste is called an electrolyte. (Britannica Kids).

How does a battery work?

- For a battery to work, the chemicals in the electrolyte cause electrons to flow from one electrode to the other. (Britannica Kids).

- A flow of electrons is an electric current. (Britannica Kids).

- The electric current flowing through the wire is what makes flashlights and other electric equipment work. (Britannica Kids).

What is a circuit?

- Electricity flowing through a circuit is called a current.(science with me)

- Electrical current needs a PATH on which to travel. This path is called a circuit. (science with me)

- If the circuit is not complete (i.e. if the loop is not closed) then electricity cannot flow through it properly. (science with me)

- Electric circuits work by allowing the flow of electric charges (electrons) from the power source through the conductive wires to the various components in the circuit. The electrons move from the negative terminal of the power source to the positive terminal, creating a continuous flow of electric current. (etutor)

How do measure electricity?

- Electric current is the rate of flow of electrons from one atom to another. (etutor)

- The current is determined by the number of electrons passing through a cross-section of a conductor in one second.

- It is measured in Ampere, amp in short, and its symbol is A. The device used to measure current is known as an Ampmeter.

What is voltage?

- Voltage is the electric force required to make electric current flow through a conductor.

- Voltage is the push that causes electrons to move.

- This force is supplied by power generators, batteries, fuel cells,

- Voltage can be measured using a device known as a Voltmeter.

- volt is the unit of measurement of voltage, and is represented by the symbol V.

How does a potato work as a battery?

- The electrolyte puts the chemicals required for the reaction in contact with the electrodes, converting stored energy into usable electrical energy. This reaction provides power to the connected device, like a light bulb or a clock.

- Different types of batteries rely on different types of chemical reactions and different electrolytes. For a potato battery, the phosphoric acid in the potato creates the intended reaction. The metal plates or electrodes oxide with oxygen for the reaction.

- The acid inside the potato forms a chemical reaction with the zinc and copper, and when the electrons flow from one material to another, energy is released.

- The potato doesn’t actually provide any electricity itself, it merely serves as the electrolyte.

- The nickel dissolves and its electrons flow to the copper. Other metals can be used, but both must be of different types.

- Eventually, the battery dies because either the nickel finishes or the electrolyte is used up.

How can boiling the potato increase the voltage?

- Softening the inner potato should reduce the resistance and let the electrons flow more freely.

Variables

Controlled Variables (for each controlled variable listed, tell how you are going to control it):

- Type of fruit or vegetable - I will only use potatoes.

- Size of fruit or vegetable - I will use potatoes of the same weight. I will weigh each potato individually and use the potatoes that are most similar in weight.

- The metals used to build the battery - I will use the same kind of metals to make the battery for each potato.

- Voltmeter - I will use the same voltmeter to measure the voltage.

- Time - I will measure the voltmeter for the same amount of time for each potato

- Distance between copper and zinc - I will use a ruler to measure the distance between them which should be the same for each potato

- Depth of the copper and zinc - measure a line on each so that they go in the same depth on each potato.

Dependent Variable

- Voltage

Independent Variable

- Temperature of the potato

Procedure

Proposed steps in your experiment (if you included a step by step in your big question proposal, you can copy and paste):

- Take 6 same weight potatoes

- Put one potato in the fridge overnight

- Put one potato in the freezer overnight

- Put one potato on the front patio

- Take one potato and put it into boiling water for 4 minutes

- Take one potato and put it into boiling water for 8 minutes

- Take one potato and leave it at room temperature

- Make a mark on each potato where the copper and zinc strips will go. Use a ruler to make sure the slits on each potato are the same distance apart. The copper and zinc need to be spaced the same distance apart on each potato.

- Place a copper strip and a zinc strip into each slit in each potato. Insert them to the same depth in each potato (for example, 2 cm apart and 3 cm deep. The exact distances you pick may depend on the size of your potatoes).

- Use a thermometer to take the temperature of each potato before starting the voltmeter

- Set the voltmeter dial to measure in the 2 V range.

- Plug the red multimeter probe into the port labeled VΩmA.

- Plug the black multimeter probe into the port labeled COM.

- connect the black probe to the copper electrode.

- connect the red probe to the zinc electrode.

- Record the voltage in my logbook

- Repeat this 3 times

Observations

1. Trials

I ran trials on five days to test if increasing the temperature would increase the voltage. I observed that there was only a small difference in the voltage and sometimes there was more voltage when the potato was colder. I kept re-trying to see if my hypothesis would be true. In the end I found that the voltage was the highest when the temperature of the potato was around 55C but if the temperature was too high the voltage dropped.

During my trials, I also tried a few things for fun. I measured the voltage of a AA battery and it produced voltage similar to a potato. I also measured the voltage of an apple and tried potatoes in series. When I put the potatoes in a series, the voltage went up, just as the sources said it would.

Chart 1: Data Collected for Analysis

|

Temperature (Celsius) |

2V Voltage (Copper – Zinc Plates) |

2V Voltage (Copper – Zinc Plates) |

2V Voltage (Copper – Nickel) |

2V Voltage (Copper – Nickel) |

|

|

White |

Red |

White |

Red |

|

20 |

1.48 |

|

|

|

|

22 |

1.43 |

|

.91 |

.81 |

|

22 |

|

|

.88 |

.90 |

|

22 |

|

|

|

.88 |

|

22 |

|

|

|

.91 |

|

55 |

1.38 |

1.56 |

|

.89 |

|

55 |

1.48 |

1.48 |

|

|

|

55 |

|

1.62 |

|

|

|

60 |

1.51 |

|

|

.90 |

|

60 |

1.49 |

|

.84 |

.77 |

|

69 |

|

|

|

.75 |

Chart 2: How Averages of Data were Calculated

|

Temperature |

2V Voltage (Copper – Zinc Plates) |

How I calculated the average |

2V Voltage (Copper – Nickel) |

|

|

|

White |

White |

White |

White |

|

20-22 |

1.46 |

(1.48 + 1.43)/2 |

.90 |

(.91 + .88)/2 |

|

55-60 |

1.47 |

(1.38, 1.48, 1.51, 1.49)/4 |

|

|

|

60 |

|

|

.84 |

|

|

|

Red |

Red |

Red |

Red |

|

20-22 |

1.40 |

|

.88 |

(.81+ .90 + .88 + .91)/4 |

|

55 – 60 |

1.52 |

(1.56 +1.48)/2 |

.85 |

(.89, + .90,+ .77)/3 |

Chart 3: What happens if you increase the number of potatoes in series?

|

Temperature |

White |

Red |

Copper - Nickel |

|

Room Temperature |

4 in series (white) |

|

1.0 |

|

|

|

2 in series (red) |

1.51 |

|

|

|

2 in series (red) |

1.31 |

|

Boiled (55-60C) |

4 in series (white) |

|

1.8 |

|

|

|

2 in series (red) |

1.77 |

|

|

|

2 in series (red) |

1.55 |

|

Mix Temperatures (Room and Boiled) |

|

3 in series (red) |

1.8 |

|

|

|

3 in series (red) |

1.55 |

|

|

|

4 in series (red) |

1.9 |

Average Data used for Analysis

|

Temperature |

Voltage with 2 Potatoes in series |

How I calculated the average |

Voltage with 3 Potatoes in Series |

How I calculated the average |

Voltage with 4 Potatoes in Series |

How I calculated the average |

|

|

White |

White |

White |

White |

White |

White |

|

20-22 |

|

|

|

|

1.0 |

|

|

55-60 |

|

|

|

|

1.8 |

|

|

Mix (Room and Boiled) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Red |

Red |

Red |

Red |

Red |

Red |

|

20-22 |

1.41 |

(1.51 + 1.31)/2 |

|

|

|

|

|

55 – 60 |

1.67 |

(1.77+1.55)/2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Mix (Room and Boiled) |

|

|

1.68 |

(1.55 + 1.8)/2 |

1.9 |

|

Analysis

Test 2

I decided next I wanted to see if I changed the electrode materials to nickel and copper. I kept everything the same except for the electrode materials. I used both red and white potatoes and measured their voltage at both room temperate and boiled. My results are on this graph. I also found that when the potato was boiled, the voltage actually went down when I used nickel and copper as electrodes. I think this might be because the phosphoric acid in the potato escaped when boiled too much. What I found was that zinc and copper produced a much higher voltage compared to nickel and copper.

Test 3

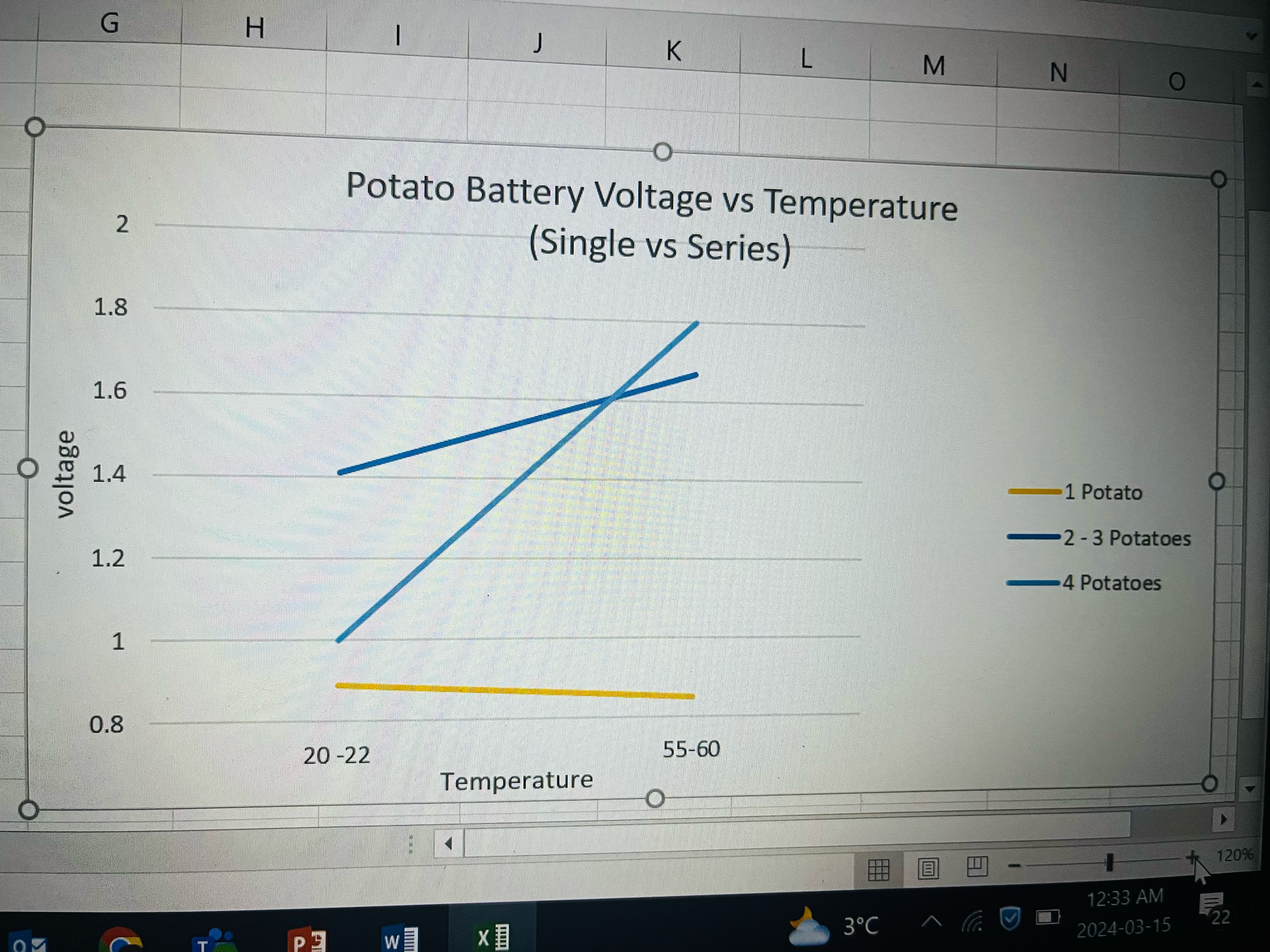

After this, I still wanted to experience and keep testing to see how the temperature impacts the voltage. I kept the procedure the same, but this time I connected the potatoes in series. This graph shows my results which were scattered but do show an increase in voltage when the potato was heated.

Analysis

I took all the data from the trials, took their average and put it into this graph. What I found was that the voltage of the potato when in series went up when the potatoes were boiled. This supports my hypothesis. What is not clear to me is why the voltage went down for a single boiled potato.

Conclusion

My hypothesis that the voltage of a potato battery would increase for boiled potatoes was partly correct as the voltage did increase when connected in series.

My conclusion is that the voltage depends on the reaction between the phosphoric acid in the potato and the electrodes, which reaction increases when boiled.

Potatoes can work as an electrolyte to produce electricity when combined with electrodes. The phosphoric acid in the potato causes a chemical reaction with the electrodes that produces electricity. Zinc and copper electrodes produced higher voltage compared to nickel and copper electrodes. This is likely because the chemical reaction between the phosphoric acid, zinc and copper is stronger than the reaction with nickel and copper.

Increasing the temperature by boiling a potato did not change the voltage very much for one potato. But when connected them in a series, boiled potatoes produced higher voltage and were able to produce as much voltage as a AA battery. This is likely because more electrons are flowing faster between the two electrodes.

Application

Sources Of Error

Cold Potatoes

On my first trial day, I froze a potato, left one outside and put one in the fridge. It was difficult to measure the temperature of the frozen potato with a food thermeter because the thermeter stick would not go inside the potato. So I took the temperature of the freezer which was -20. The voltage was fluctuating alot on the voltmeter and I am not sure if the reading was accurate because it was the same voltage as the potatoes at room temperature. I decided not to do more trials with frozen potatoes because of these issues.

Voltage Meter

On my first trial day, I set the voltmeter at 20V. Because the potato was producing low voltage I changed this to 2V on the next trial. So I am not sure if the data from the first day is accurate but I used it in my analysis. The reading of the voltage meter fluctuated in its readings really fast and went up and down; I waited for it to stabilize and then took the reading.

Citations

https://kids.britannica.com/kids/article/battery/390651

Iihttps://www.sciencewithme.com/learn-about-electricity/

https://www.etutorworld.com/5th-grade-science-worksheets/what-is-electricity-worksheets.html

https://dragonflyenergy.com/battery-electrolyte/

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20131112-potato-power-to-light-the-world

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank my teacher Mrs Ghosh for her guidance and for helping the kids at Brentwood school to participate in the Calgary City Science Fair. I would like to thank my Masi and my mom for all their help with my project.